A female’s innovative bionic hand has been integrated with her bone and nervous system through experimentation.

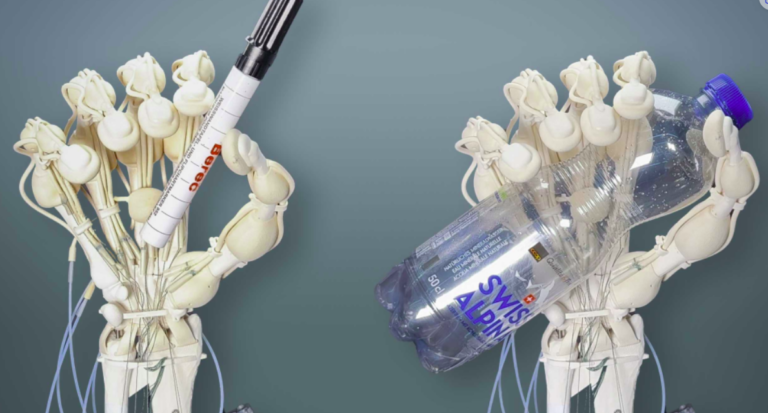

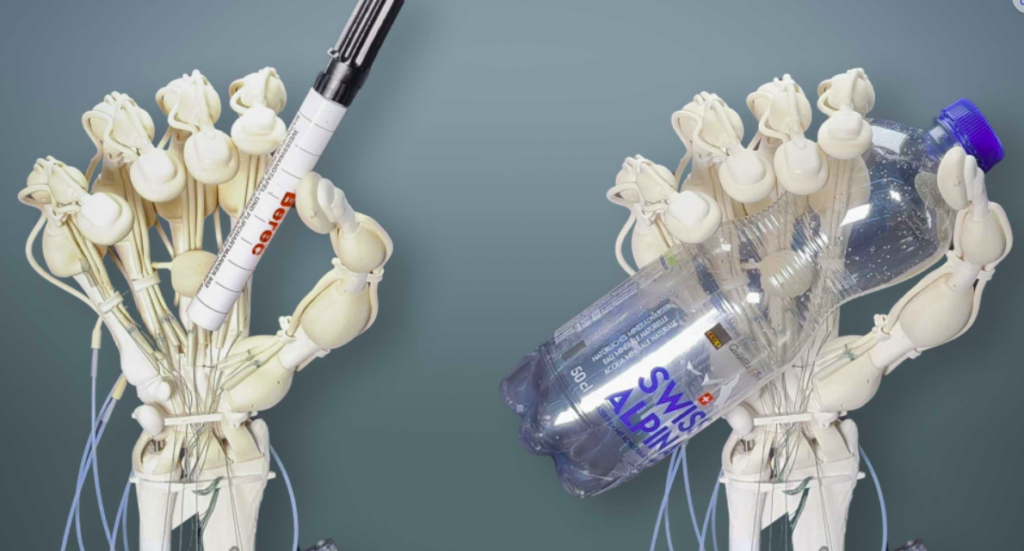

Although they have advanced significantly, many prosthetic hands are still too cumbersome and awkward for daily use. Most prosthetic hands are not only unable to mimic the dexterity of a real hand, but they are also unable to provide the user with neurological input, which eliminates tactile or kinesthetic sensation. However, a new kind of prosthetic is coming soon because of a program called DeTOP: An unparalleled range and sensation is provided by a bionic hand that is connected to the user’s bone and nervous system.

The term “dexterous transradial osseointegrated prosthesis,” or “DeTOP,” refers to a partnership of Swedish, Italian, Swiss, and British research institutions. The companies have been collaborating since 2018 with the goal of developing a prosthetic limb that can replicate the dexterity of a natural hand in addition to sensing texture and pressure. In 2019, DeTOP produced its first working prototype. Shortly after, it started assisting a Swedish woman whose lower arm had been severed twenty years before in a farming accident. This woman would be the first candidate for a bionic hand in DeTOP.

The success of the prototype over the last four years is described in full in Science Robotics’ October cover story. According to reports, the woman, named Karin, is able to accomplish 80% of the tasks that a natural hand can do with her bionic hand. Compared to her previous situation, which was characterized by limited movement and nearly continual phantom limb pain, this is a major improvement.

In a statement for Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, an Italian university involved in DeTOP, Karin said, “It felt like I had my hand in a meat grinder, which created a high level of stress and I had to take high doses of various painkillers.” She went on to say that traditional prosthetics were not useful or pleasant enough to warrant their use. “This research has improved my life, so it has meant a lot to me.”

Karin had to finish a rehabilitation regimen to help her forearm bones—the radius and ulna—regain strength before she could begin using DeTOP’s bionic hand. (As partial amputations are less common, bones may deteriorate thereafter.) She also had to use virtual reality to practice controlling her missing hand. The bionic hand was then electrically linked to Karin’s nervous system and bonded with her bones. Karin can feel pressure and texture on each finger and manipulate the bionic hand thanks to electrodes inserted into her forearm.

Data released in Science Robotics indicates that since obtaining the bionic hand, Karin’s mobility and general quality of life have increased. Her limb discomfort, sleep and work-related difficulties, and phantom pain have all greatly lessened.

Although it’s unclear if DeTOP intends to build upon its first working bionic hand, the program’s successes could spur the development of a new generation of amputee prosthetics.